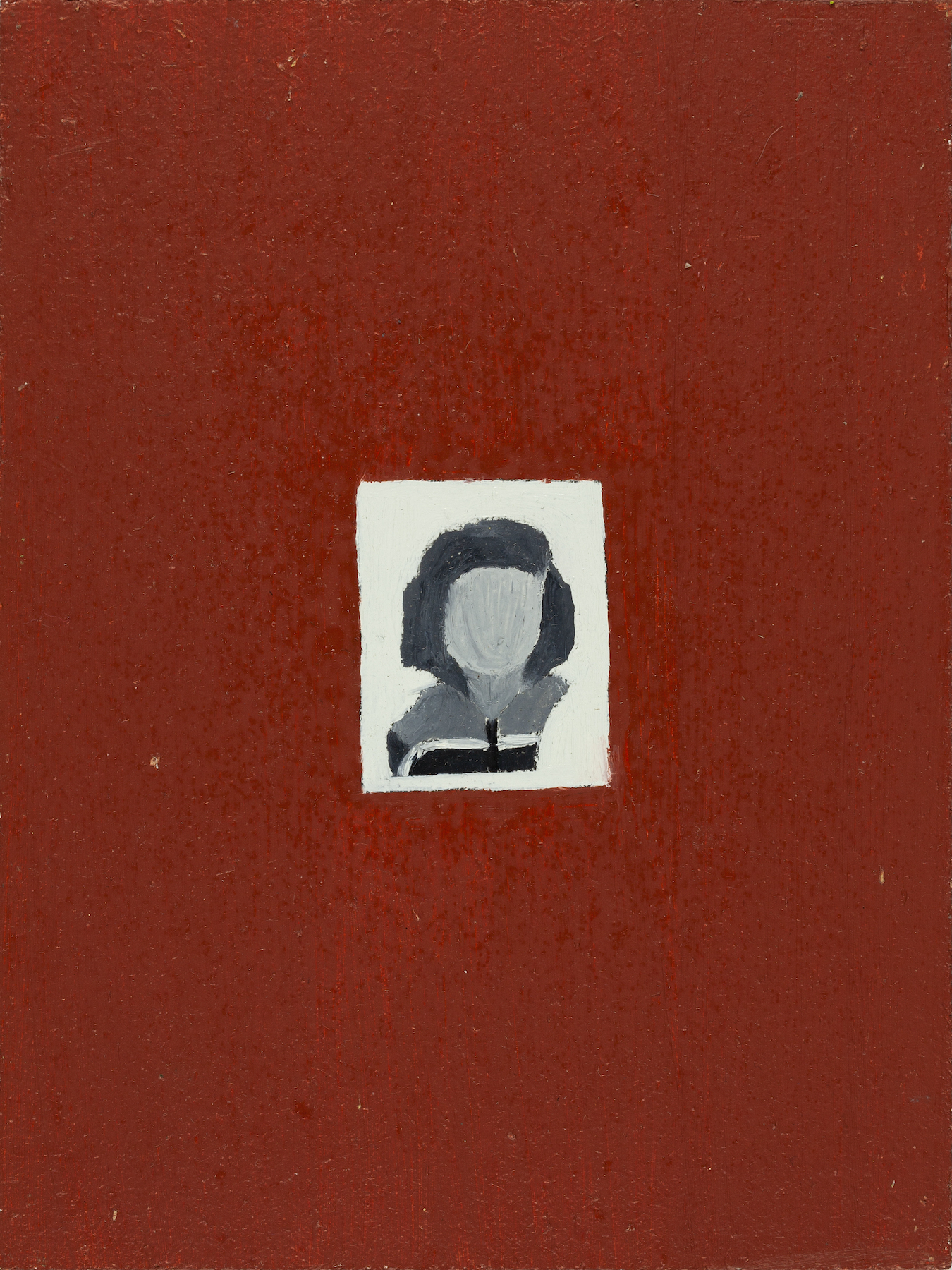

Russian social anthropologist, Ilya Utehin, talking about everyday life of Soviet communal apartments refers to the phenomena of a family photo album as a catalogue of human social behaviour patterns. One can see a photo of someone standing and smiling or some people on the beach, or on a trip, in front of the monument, or dancing, or drinking,

but the amount of subjects is limited. People's behaviour draws familiar patterns. They look so similar that one can replace the faces of characters inside the photo album. This effect is a leitmotif in ”Private Chronicles. Monologue” - Vitaly Mansky's documentary. The filmmaker depersonalised amateur home-video and reconstructed the whole life of a typical Soviet man piece by piece from dozens of found footage fragments. He creates his protagonist from scraps of dozens of different characters.

Despite considering the repeatability of behaviour patterns to be a common feature of humankind, specifically this repeatability, according to anthropology and culture studies, is more pronounced under totalitarian regimes. A person who was born in the Soviet Union unconsciously shared destiny with millions of compatriots. A person who was born there and also has seen its collapse is still keeping these patterns both as a memory about their own childhood, and retention of a disappeared world.

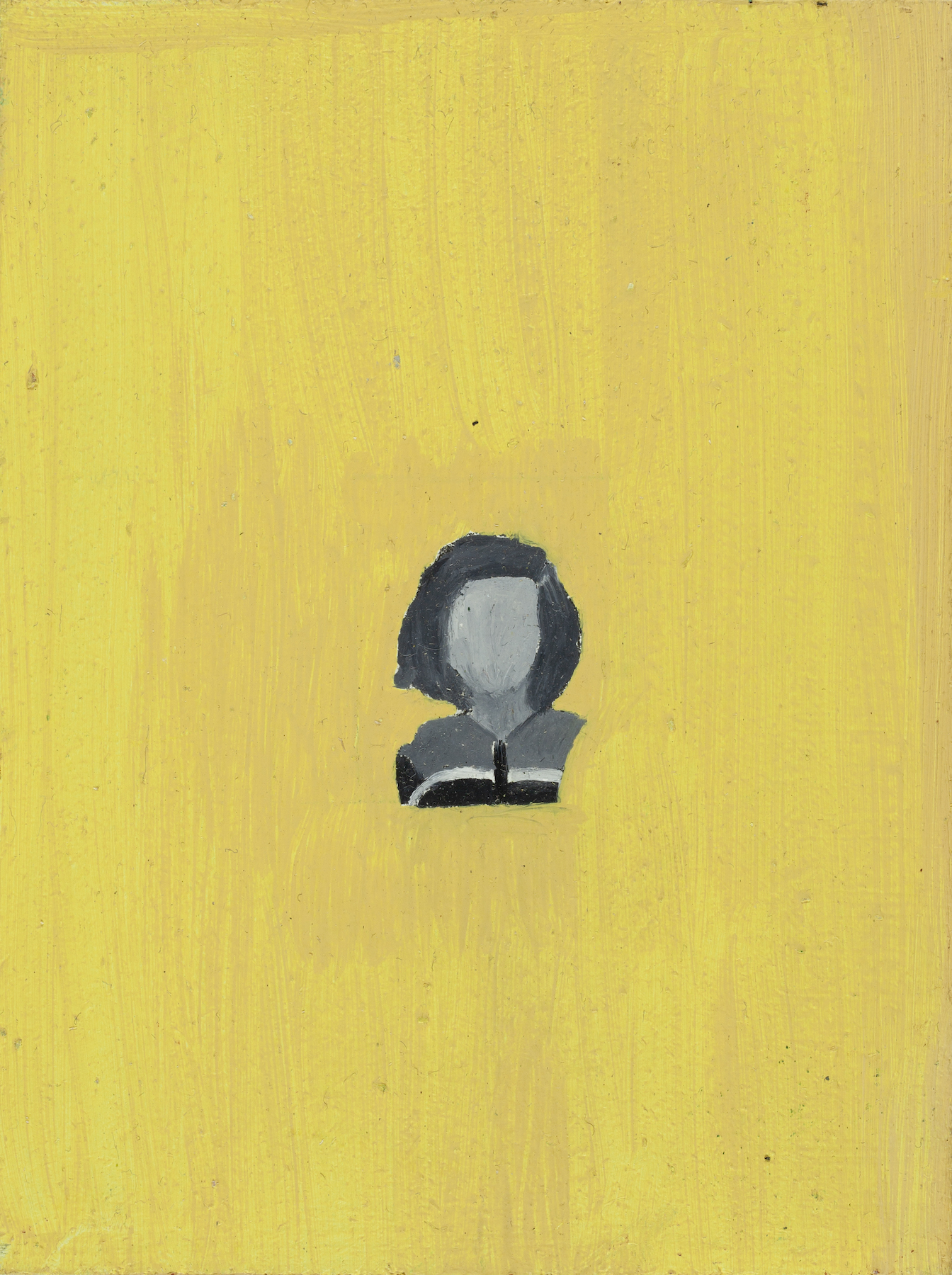

Sasha Rotts uses the same effect in her painting. Despite the importance and intimacy of these images for the author, they are partly impersonal. School, same as the army, depersonalised a character. Those who had experienced the Soviet school's uniform could perfectly understand this comparison. The state participated in the lives of its citizens in a role of a master, like George Orwell's Big Brother, and even more important: people were used to thinking that it was a natural order of things. It was truly a predetermined order of how things worked in the USSR. State delivers you, educates you, uses you, and then, at best, you'll be buried with honours in or, at worst, consigned to the dustbin of history. For the majority of young Soviet parents, it was natural to think that school was supposed to take care of a child's personality.

The social system worked as a conveyor transporting a person from maternity hospital to kindergarten and then to school and so on leaving aside a family.

In Sasha’s case, we were faced with a paradoxical comeback of personal family values by the back door, through the succession of generations that went through the same depersonalising structure one by another. Several generations of Sasha's family: firstly, grandfather, then father, elder sister, and then Sasha herself, used to go to the same local secondary school. Referring to the famous Pink Floyd's animation movie, The Wall, Sasha claims: "We don't need no education! We don't need no thought control!" Instead of becoming "just another brick in the wall" she is breaking through this wall like Pinocchio through the Master's Carlo's canvas with a fireplace depicted. Artist's curious nose steers her to a new school located in the city center, and there a completely different story begins. It's true that our childhood was the time when the Soviet Union started to fall apart, but sometimes it gave us a wonderful play of colours as an old broken TV-set. Our school that took place at the very end of the Soviet era and the turn of the millennium still pretended to be our Mother and Father, our mentor, educating us and putting knowledge into our empty heads, guiding us on our way. We still remember our school being like this. And our memories are the same.

text by Pavel Rotts