The project’s main topic is the displacement of the Ingrian population during and after WWII.

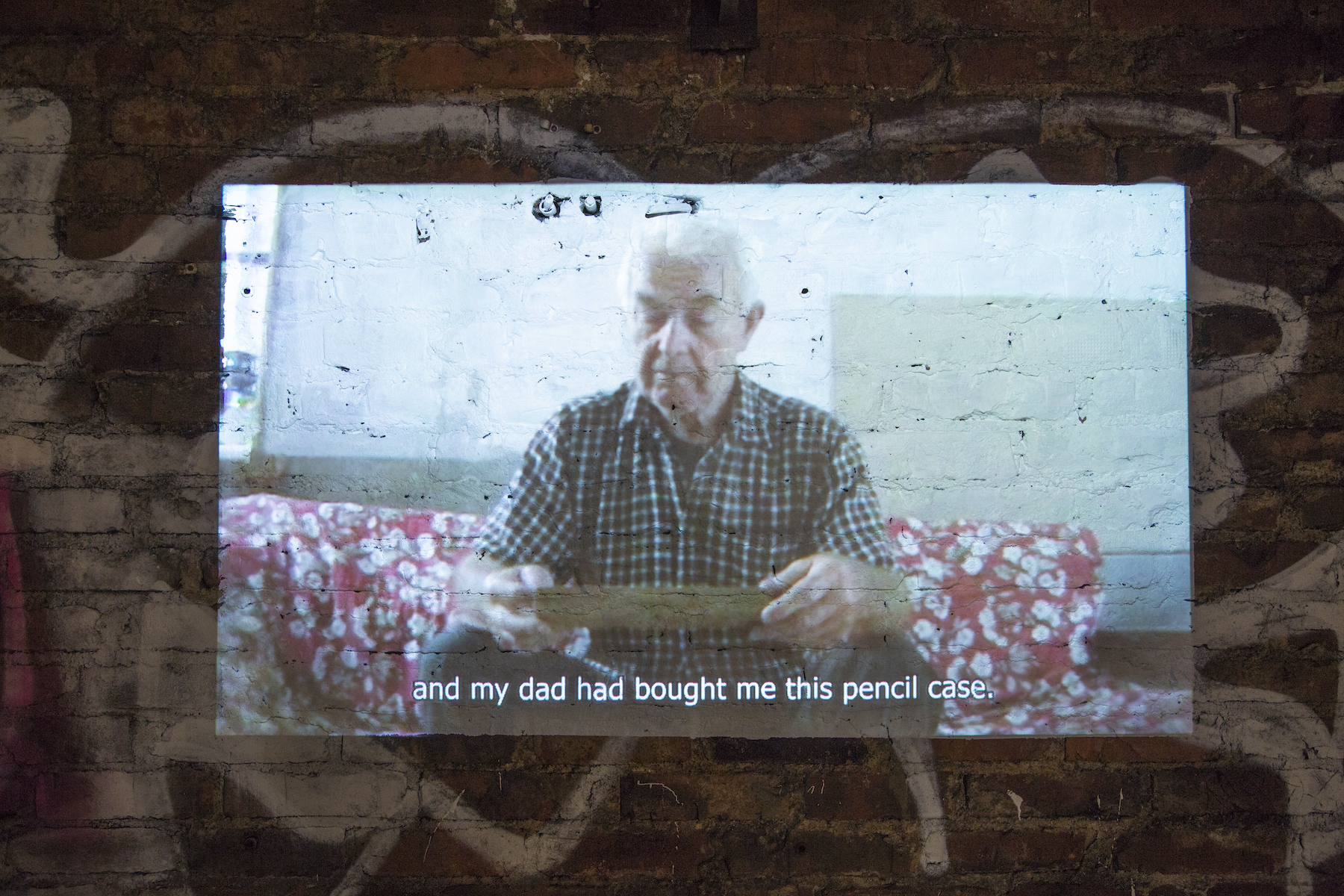

‘Pencil case’, in the Russian language, sounds similar to the word "penal" (пенал). Penal labour was a main and common feature of both Nazi and Soviet concentration camps, and in this project’s title, becomes a play on words, and a reflection on grief.

My grandfather received a pencil case as a gift from his father when they lived in Finland during the Second World War. For me, it became a symbolic representation of my grandfather's life.

The story started in Kuttusi village near Leningrad where many Inkeris, including the family of my grandpa, used to live. During the war, they were occupied by Nazi forces and sent to Klooga, a labour camp in Estonia. Fortunately, the Finnish government came to an agreement to take all Inkeris from Klooga into Finland in 1943. The family arrived in a small village near the Lohja. The household where they lived and worked still exists.

After the war, they were forced to come back to the Soviet Union. They were not allowed to live near Leningrad anymore. They were considered as politically undesirable and sent to a lumber-camp in the northern part of Karelia.

Despite the White Sea-Baltic Canal being built 15 years prior, the family inhabited the same barracks where Gulag inmates used to live. Working with wood in lumber-camps was the most typical labour for Gulag inmates, and the family followed in this line of work.

The wood industry was exporting resources, but at the same time leaking information about penal labour. This became a problem for the foreign policy of the new-born country. The Ad Hoc Commission was sent to the Soviet Union, but deceived by the Soviet intelligence services. Products of Soviet penal labour were widely spread outside of the USSR.

Penal Labor installation on KANAVA V exhibition